Old Souls, Young Voices: Neo-Soul

Note: Welcome to Edito, the written space of Literal Radio that centers music-shaped, evolving, and deepening cultures. Every two weeks, you’ll be invited into the stories behind genres, scenes, and sounds. Enjoy the read.

Before we shake the dust off the musical past and revive it in our memories, there’s an important point that must be made: R&B in the mid-1990s did not need saving. With its growing commercial power that would soon dominate the mainstream, R&B was in a phase one could only describe as thriving. Aaliyah was releasing songs that made everyone smile, while Mary J. Blige was bottling her pain in hip-hop. In the ’90s, the “cool” image in R&B was the work of gangsters, and that image was shaped by a wave of innovative producers. Names like Teddy Riley, Babyface, Jermaine Dupri, and Timbaland functioned as the quality control unit of Black music.

Soul on the Rise

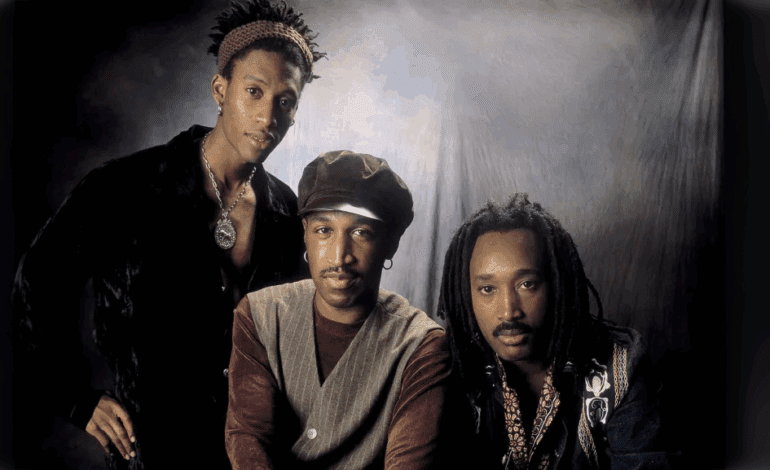

Yet, while these producers crafted a glossy, commercial R&B sound, a deeper voice began to emerge—one that would breathe new life into a long-standing tradition. Against the mainstream narratives that dominated the radio, neo-soul artists stepped onto the scene to create a contemporary variant of the ’70s soul aesthetic, blending it with influences from other traditions. Neo-soul nodded back to the era when Marvin Gaye channelled social unrest into personal expression and vice versa. This new sound wasn’t foreign; it was rooted in progressive soul and jazz-funk. By the 1990s, it had been nurtured by British soul artists like Sade, Soul II Soul, and Omar, as well as American pioneers such as Prince, Tony! Toni! Toné!, and Me’Shell Ndegeocello. Many of those who pioneered neo-soul were children raised within the consciousness of the Black Power movement and a rich soul heritage. This cultural legacy would inspire the perspectives and creativity of D’Angelo, Maxwell, Erykah Badu, Lauryn Hill, and Jill Scott.

We’re Not Back, We’ve Just Arrived Anew

Artists like D’Angelo, Maxwell, and Badu released landmark albums— Brown Sugar, Maxwell’s Urban Hang Suite, and Baduizm, respectively—anchored by vocals that echoed the greats of the 1960s. Their success proved that this emerging consciousness was not a niche genre, but a critical and commercial force. The term “neo-soul” was coined by Motown Records executive Kedar Massenburg, who sought to market this forward-looking attitude that paid homage to music’s soulful past. Massenburg, who worked behind artists like Badu and D’Angelo, tried to define this blend of soul, R&B, jazz, and funk. However, as the music industry made room for this retro sound, Pitchfork writer Clover Hope criticised the framing of new soul artists as saviours returning R&B to its “roots,” a view that ignored how much of the genre had always been shaped by innovation. Contrary to that narrative, for many, neo-soul was simply a continuation and expansion of an existing tradition.

Can You Be Boxed In?

Genres often need names to help people navigate them. Neo-soul, in that sense, served as a useful label for this final wave of new genre-making. But to many within the community, it also felt like a marketing tactic. Most artists preferred to describe their music as just “soul” or “R&B,” believing the term implied that soul music had ended and needed revival. For Massenburg, it may have been an act of preservation, but black music has always found ways to break moulds. After all, the lines between jazz, soul, R&B, and hip-hop have never been sharply drawn.

In this blurred map of Black music, Erykah Badu—often referred to as the “godmother of neo-soul”—was always one of those shapeshifters who worked to complicate the very definitions of black identity and black music. Baduizm marked the beginning of her ritual of artistic rediscovery. According to Kelefa Sanneh, before she was a singer, she was a rapper and dancer. Raised in a working-class Dallas neighbourhood, Badu grew up with Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, and Chaka Khan. She witnessed the rise of hip-hop and fell under the spell of New York’s scene. Today, one can clearly hear that her style leans on the soft harmonies of the ’80s, too. Baduizm owes as much to Roy Ayers as it does to her own humble hip-hop cool.

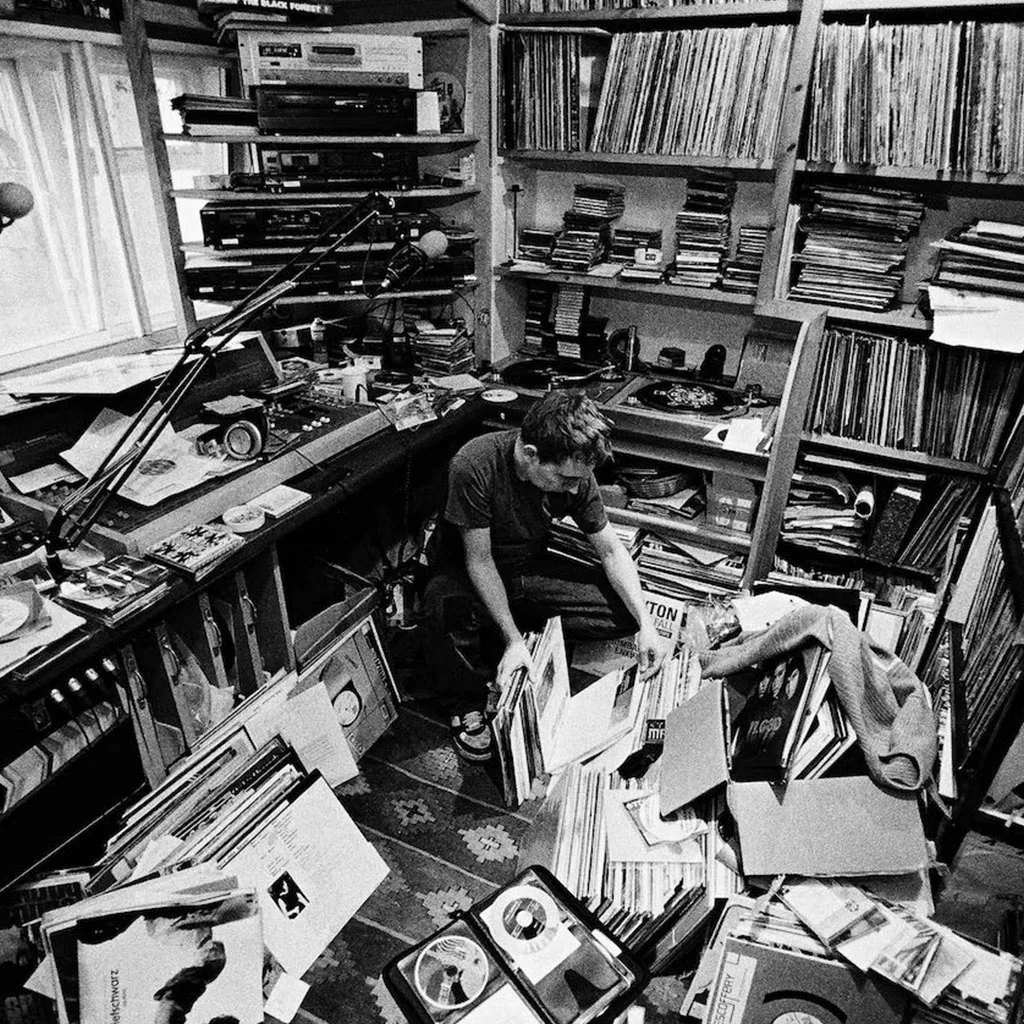

A Collective Vision: The Soulquarians

By 1998, as the neo-soul wave reached its peak, a group of like-minded artists came together to push it further. They called themselves the Soulquarians and gathered at Electric Lady Studios, originally founded by Jimi Hendrix, to produce some of the most iconic recordings of the era. Common’s Like Water for Chocolate, D’Angelo’s Voodoo, and Badu’s Mama’s Gun were all crafted there, as artists swapped grooves and riffs in communal creation. The driving force behind these sessions was a commitment to creative independence, often in direct opposition to the dominant commercial R&B climate.

This new interpretation of the soul was not merely a torchbearer of tradition; it didn’t follow any written rules. While neo-soul developed a recognisable identity, it gained strength from its fusion with hip-hop. As Russell Elevado put it: “All these people had a vision, and they’re finding people of the same vision, at the same time. I think where it stems from is these hip-hop grooves — and it’s coming out of the old ’70s funk records, and R&B. But I think hip-hop was the one element to fuse these people together.” In writing about the Soulquarians’ sound, Rhys Thomas noted their complex melodies, dynamic arrangements, and richly textured instrumentation. He argued that these elements, now common in contemporary hip-hop, owe much to the legacy of the Soulquarians. Though short-lived, their influence still resonates in today’s musical collectives.

Post-Impact with a New Generation: Soul Without the Neo, Hop Without the Hip, B Without the R

In the early 2000s, the movement slowed. As Tyler Lewis put it, “The industry, which already has a hard time with unapologetic and complicated black artists, had no idea what to do with all these enormously talented individuals who rejected entire marketing campaigns designed to break them to the record-buying public. As such, albums were shelved or delayed or retooled, and artists were dropped from major labels and forced to go it alone, making the first decade of the 21st century the least soulful”. Mainstream music shifted toward R&B-pop hybrids that favoured carefree exuberance over social commentary. Yet this climate also gave artists like Badu the freedom to redefine themselves as creative forces outside any one genre. In fact, Sanneh’s portrait of Badu suggests the “neo” label could now be dropped—not because her music had gone out of style, but because it had become harder to categorise, and perhaps easier to simply enjoy.

By the 2010s, the contemporary soul aesthetic of the ’90s had evolved. Artists blended with new genres and experimented with technology, heading in multiple directions. Neo-soul’s backwards-looking vocals and live instrumentation lost some cultural relevance. Still, its sound lives on, updated and revitalised by artists like Frank Ocean, Kendrick Lamar, Anderson .Paak, Thundercat, Little Simz, and Tyler, The Creator. Meanwhile, Badu’s place in soul continues to echo through a new generation of artists, including Janelle Monàe, Solange, SZA, and many others. Solange’s A Seat at the Table uses soul music as both balm and weapon, channelling its healing and expressive powers.

In short, like many genres, neo-soul didn’t die. It adapted, evolving in response to shifting cultural climates. Today, it re-emerges through artists like Hiatus Kaiyote, Cleo Sol, Yaya Bey, Olivia Dean, and Jorja Smith—not as a revival, but as a reinvention.