Neither American nor Caribbean but British: UK Street Soul

Note: Welcome to Edito, the written space of Literal Radio that centers music-shaped, evolving, and deepening cultures. Every two weeks, you’ll be invited into the stories behind genres, scenes, and sounds. Enjoy the read.

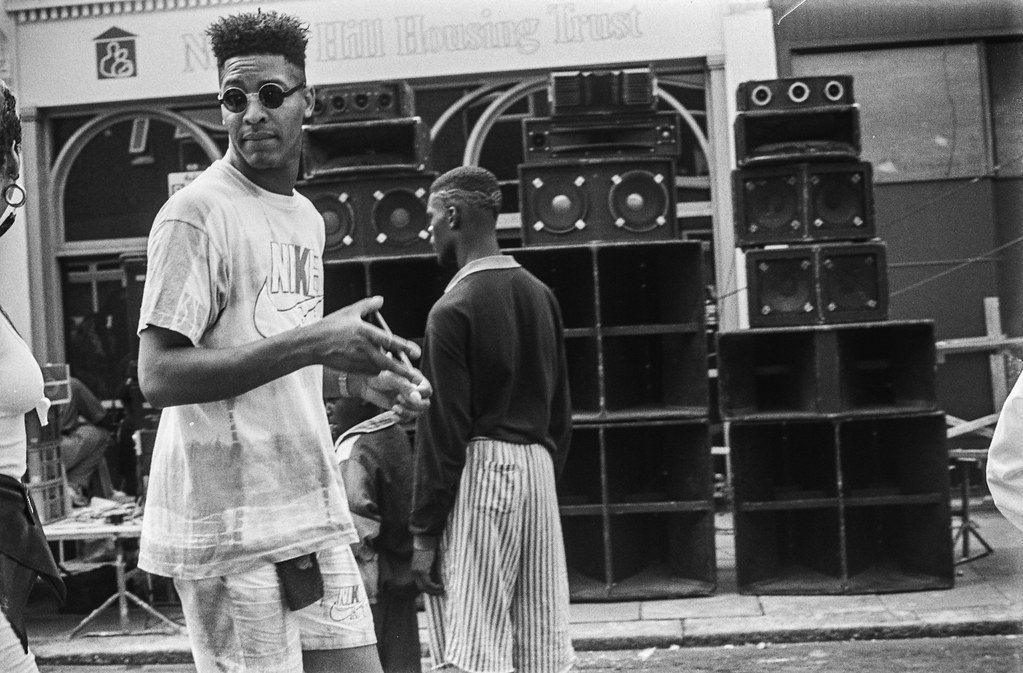

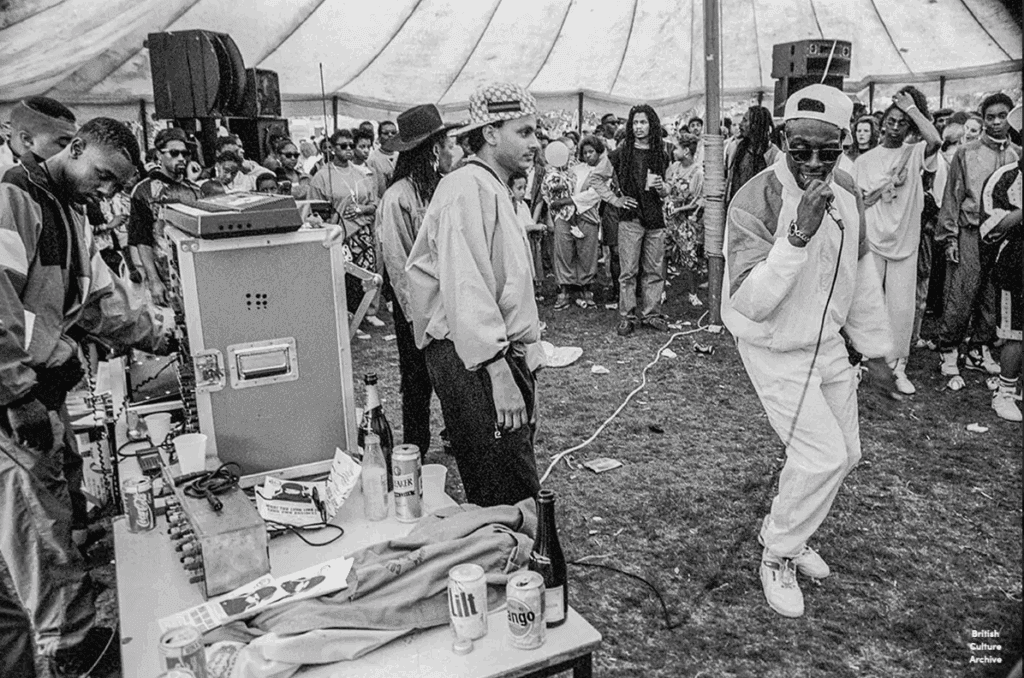

By the time the ’80s were welcoming the ’90s, the United Kingdom had moved beyond welcoming acid house and rave to embracing them wholeheartedly. British dance music, which had found a new home in clubs, abandoned industrial warehouses and empty spaces, brought together disparate musical communities with the Second Summer of Love, also known as the summers of ’88-’89. While acid house was dominating the dance scene, the inner-city neighborhoods of the United Kingdom were also hearing the sound of a youth movement that would come to be known as street soul. This music, carrying the multicultural structure of Britain’s inner cities in its DNA, was influenced not only by hip-hop, soul, and R&B traditions but also by reggae and sound system culture. To hear the story of this underground soul community, we mark our location as Hackney, London.

As is often the case with most creative productions flourishing in multicultural environments, before that vibrant cultural scene was displaced by cocktail bars, galleries, and high-rise housing—that is, before that all-too-familiar gentrification recipe was applied—Hackney was a slum neighborhood that stood out as a creative and cultural center for Black British artists. It offered a mixture of middle and working class, wealth and poverty shaped by different cultures. With its aspirations, cultural and class differences, Hackney was a place that hosted immigrant groups who set foot in the city, attracted by its largely industry-based economy. In precisely such an environment, Hackney became one of the major centers for UK street soul.

Agbetu’s laboratory: From analog devices to street soul

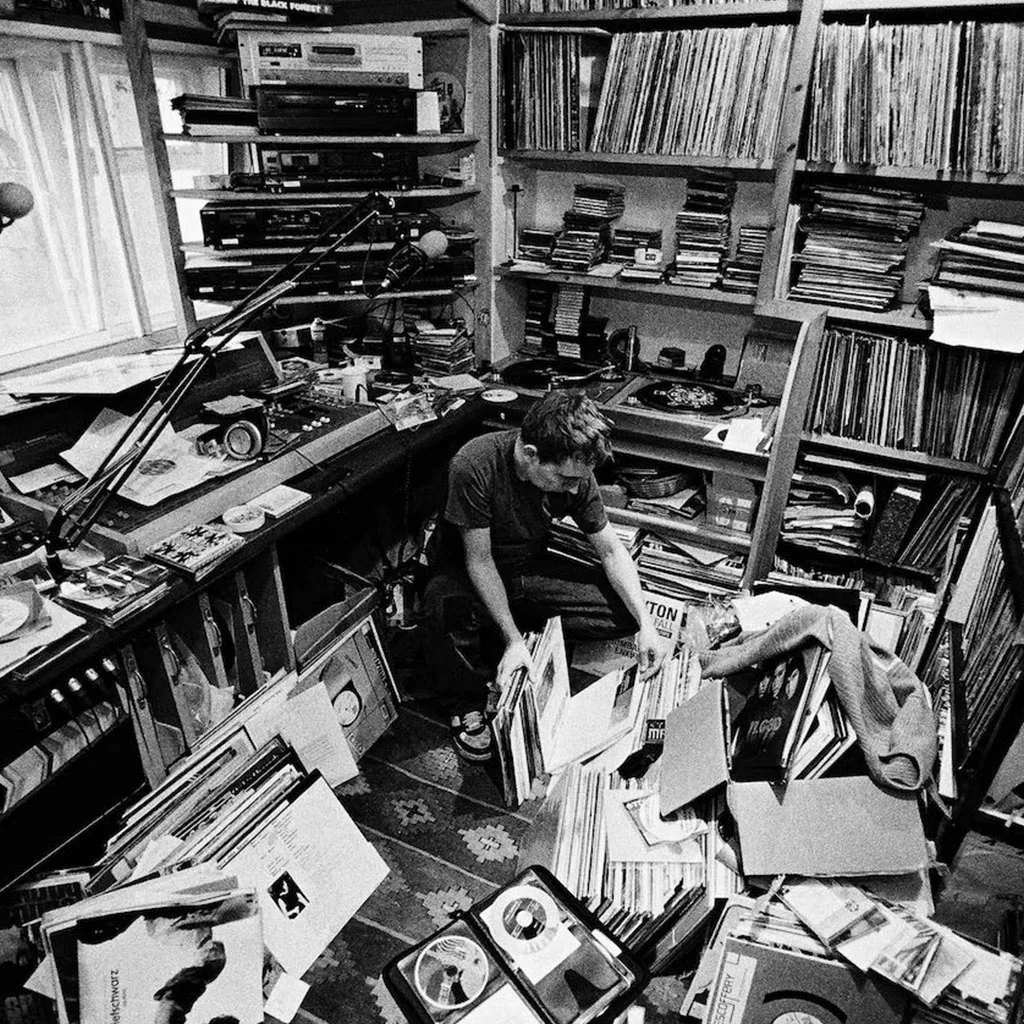

This new sound, born as a subgenre of UK soul, was certainly not solely identified with Hackney; it had established relationships with other neighborhoods like Notting Hill, Harlesden and cities like Manchester or Birmingham that had strong ties to the genre. But Hackney watched closely as Toyin Agbetu, one of the main architects of street soul, searched for his own sound in his bedroom, and witnessed the genre’s low-cost production style and independent spirit take shape. For example, Agbetu, a former computer programmer, used a Roland SH-101 or Juno 106 to create bass lines and a Yamaha TX7 or Akai S950 sampler with a simple electric piano preset to imitate the Rhodes piano sound. This approach gave the genre its signature, a more raw and sincere timbre, as well as a musical identity characterized by powerful drums and bass.

Creators looking for a softer and more emotional sound despite the popularity of acid house formed the foundation of the genre by combining soul and R&B influences with electronic production. The must-haves were a BPM that felt more like flowing water than a choppy sea, lighter rhythm beats (808), contemporary R&B or soul vocals with personal and emotional lyrics that also made room for social messages, 80s-style synth melodies, hip-hop-inspired drums, and elements of funk classics.

What made UK street soul unique was that it created a form of expression that reflected the life and cultural identity of inner-city black communities. It was the adoption of an independent, grassroots approach to production and distribution that drew on the spirit of the street with powerful sounds and narratives. On the other hand, American soul already had an established industry, with well-known record companies providing artists with big-budget productions and marketing. It had been shaped by gospel traditions and church culture.

British sounds wandering through immigrant streets

While civil rights and social justice issues were being addressed, there was an atmosphere on the streets across the ocean that touched more on British youth and their daily lives, and also poured out its notes in favor of love. In a way that made it distinctive, British street soul was closer to immigrant and diasporic identity. The 1980s was an important period of identity construction for black communities in Britain. The second generation of the Windrush generation was building a unique Black British identity by combining the Caribbean culture of their parents’ homeland with immigrant life in Britain, shaped by both cultural and class transitions. That street soul was a product of this construction can be heard in this interview African-British Agbetu gave to Resident Advisor:

“I was a product of my environment. I lived on an estate, we were working class so the music, the street soul was just a reflection of what we were and where we came from. The fusion was culturally a reflection of everything I’d experienced; all different genres, all different messages.”

The creators of the genre were creating original British expressions of their cultural heritage rather than simply reproducing American or Caribbean forms. It was neither entirely tied to Jamaican music (reggae or lovers rock) nor was it entirely a copy of American R&B or hip-hop. It was something entirely new: a sound reflecting the experiences of Black youth growing up in Britain.

The vibrant soul movement at the heart of the underground

There were two major British inspirations on the musical canvas of UK street soul: Lovers Rock and Brit-Funk. Brit-funk groups that proved to Agbetu that the UK could make its own dance music inspired him, and so the first wave of UK dance music in the early 80s formed the basis of street soul. Most of the first underground soul records in the UK also came from small dance music labels like Elite Records, which had pioneered the process. Under the alias Master Tee, Agbetu first signed Rosaline Joyce’s Lovers Soul album, then formed Deluxe, one of the most respected groups of the genre, with Delores Springer, whose background was in lovers rock. Lovers rock, Britain’s emotional reggae variant, had a close relationship with street soul. It was both a form of expressing love and self-discovery for Black youth and a music genre that flourished with the support of independent record companies.

In short, the creators had nothing to do with big producers, mainstream media, or being an alternative to American soul music. The underground soul community found its place in black-majority neighborhoods across Britain, in bedrooms that served as studios for their low-budget productions, in independent record companies, and in the hearts of loyal underground listeners.

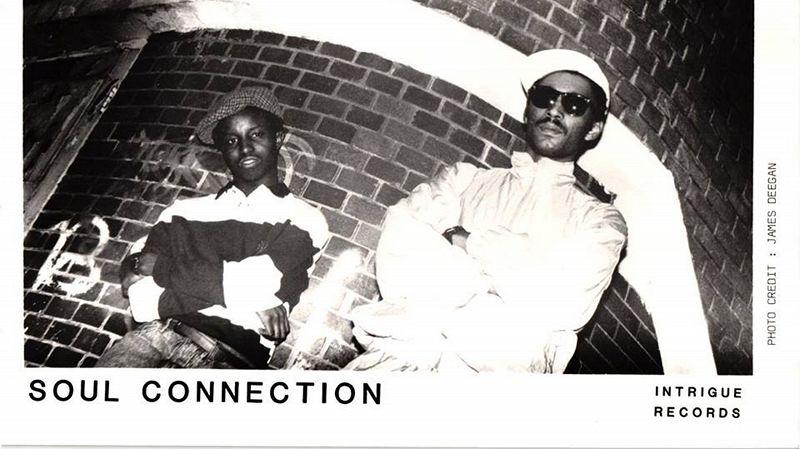

It developed as another striking DIY (Do-It-Yourself) sound of the era in clubs, blues parties, and pirate radio stations. The genre became popular with groups like Soul Connection, Deluxe, Special Touch, Fifth of Heaven, and Cool Down Zone, and independent labels like Intrigue, Soultown, Jam Today, and TSR (Top Secret Recordings). Pirate radio stations such as LWR, Supreme FM, and Invicta Radio, which played a crucial role in the spread of genres such as soul, funk, and reggae, were among the most important players in helping street soul tracks that mainstream radio was not inclined to play to be heard and reach their audience.

Manchester sound line: Clubs, women, and powerful vocals

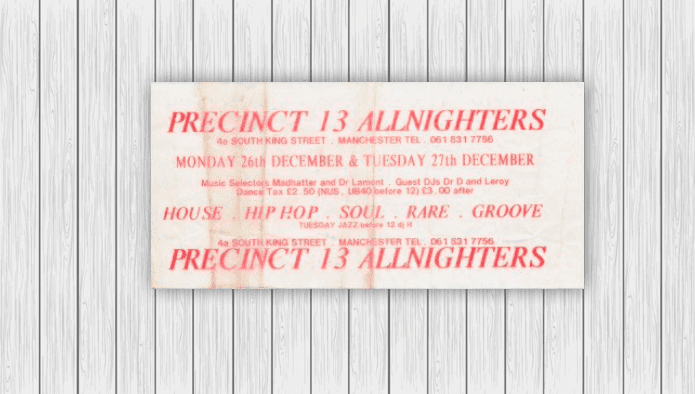

While the sweet vibrations of street soul echoed from Birmingham to Bristol, these radios were also important for another powerful scene where the sound gained new dimensions and developed in clubs, like Manchester. The city was home to some of the genre’s finest: Fifth of Heaven and the powerful female vocalists Diane Charlemagne and Denise Johnson, who shaped Manchester street soul. Mark Rae, founder of Manchester’s Grand Central Records, tells how Fifth of Heaven’s Just a Little More became a classic in favourite clubs like Precinct 13.

On the other hand, in his book Northern Sulphuric Soulboy, Rae wants to tell the world the story of street soul, even though the mainstream has turned its face away and there are more resonant names like Soul II Soul and Omar:

“The Madchester stuff was a story being sold to the outside world. All the heads that had the record stores in Manchester were selling jazz, funk, soul and hip-hop.” “Soul music mixed with hip-hop that ranged between 80 bpm two-step and 105 bpm bounce—it didn’t fit in with a predominantly white crowd on ecstasy,” says Rea. “This is why these stories are sometimes forgotten or ignored. Street soul is a message of love from the often forgotten inner cities of Britain.”

Longing For Better Content?

No one belongs here more than you do.

Read thought-provoking articles that dissect everything from politics to societal norms. Explore critical perspectives on politics and the world around us.

Also, you can follow us on Instagram