Heaven is found on the dancefloor: Chicago House

Note: Welcome to Edito, the written space of Literal Radio that centers music-shaped, evolving, and deepening cultures. Every two weeks, you’ll be invited into the stories behind genres, scenes, and sounds. Enjoy the read.

On July 12, 1979, rock fans in Chicago declared the “death of disco” at Comiskey Park. During a baseball game, what came to be known as “Disco Demolition Night”, saw over 20,000 disco records destroyed. Banners reading “disco sucks” were hung across the stadium. The destruction triggered near-riot chaos on the field, making national news.

When listening to people from that era, you can hear how disco had begun to feel stale to some listeners—too formulaic, too commercial. But the symbolism behind burning records was far heavier, carrying a message meant to stir the masses. According to Vince Lawrence, many of the records destroyed that night weren’t even disco—they were simply made by Black artists in other genres. Chicago writer Marguerite L. Harrold recalls the event in horror: “Watching it on television, it was like watching a Klan rally. It was terrifying. People who knew, knew that this wasn’t about disco. This was an effigy of burning us, a way to make us unalive, a way to take away something that you feel threatened by in a very violent way, because it started a riot.” The media storm that followed exposed deeper social prejudices, such as homophobia.

The Revenge of Disco

Disco was driven underground but rose from the ashes in a brand new form. In New York, its decline paved the way for the birth of hip-hop. Meanwhile, in Chicago, a different but similar movement was taking shape: It was called house music.

DJs like Frankie Knuckles, Ron Hardy, and The Hot Mix 5 radio collective began mixing Italo disco, funk, vintage disco tracks, and the electro-pop of Yellow Magic Orchestra and Kraftwerk, creating a vibrant new bouquet of dance sounds.

The Warehouse, a members-only gay club, became the cradle of house music, and thanks to its first resident DJ, Frankie Knuckles, Chicago discovered its new rhythm.

Known as the “Godfather of House,” Knuckles used tape machines and drum machines to remix, speed up tracks, and extend their most euphoric moments. His innovative style defined the early house sound that local producers began to emulate.

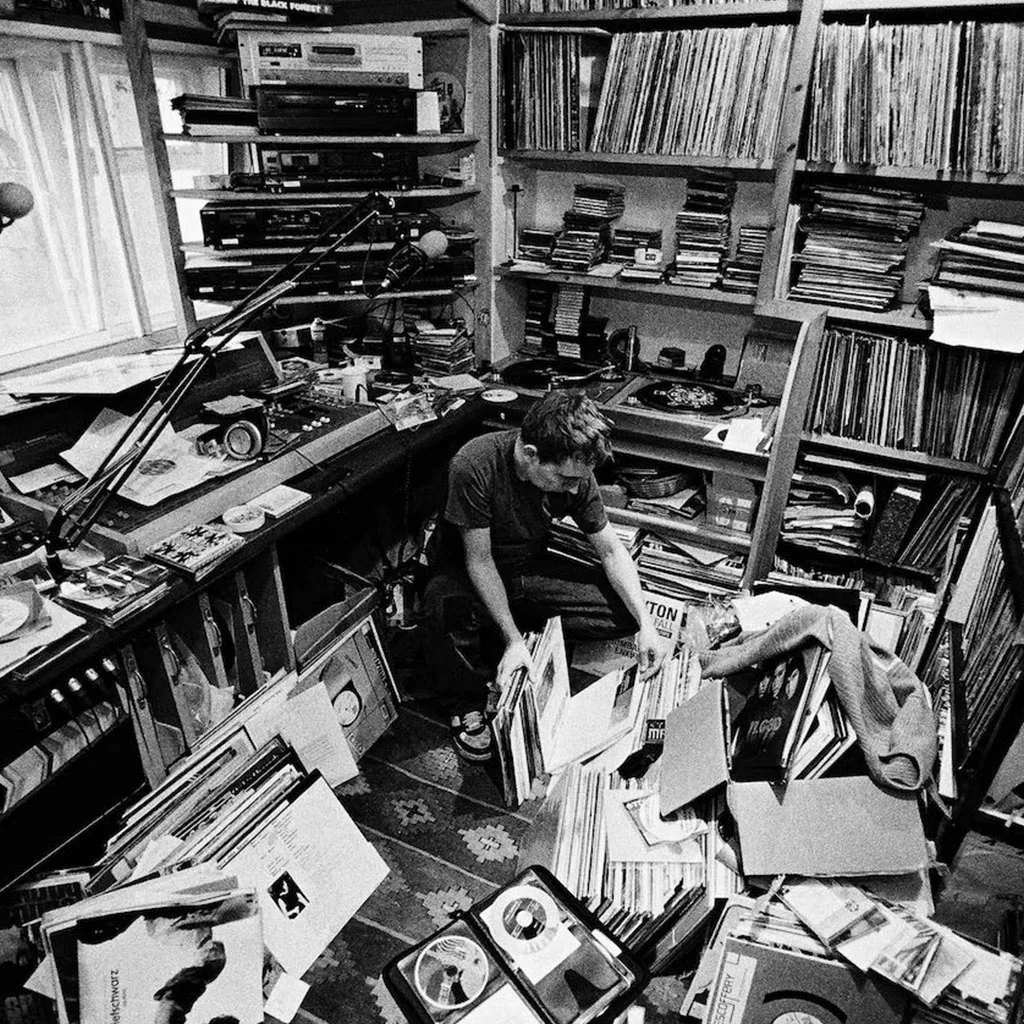

Faced with limited DJ equipment, early house producers creatively chopped and looped disco records to overcome their constraints. Most didn’t own mixers or expensive gear.

Ironically, failed commercial products like the Roland TR-808 and 909 drum machines became vital tools for young hip-hop and electronic producers who bought them cheap and gave them new life. These creators layered effects and synths to keep the fun and inventiveness alive, chose a steady 120–130 BPM heartbeat, and embraced the signature 4/4 house rhythm. As this new sound grew in popularity, record stores began shelving it under a new label: house.

Together on the Dancefloor

Speaking of the spirit of the times, Lady D puts it this way: “People wanted to dance. It was all about the music. It was all about the DJs, and it was all about getting together.” Early pioneers like Mr. Lee, Chip E., Jesse Saunders, Steve “Silk” Hurley, Farley “Jackmaster” Funk, Marshall Jefferson, and Larry Heard (aka Mr. Fingers) were among those DJs everyone wanted to get together.

For many, this music and the community it created offered an escape from earthly struggles—especially as the AIDS epidemic began claiming lives on the dance floor. Knuckles once said, “House music is a church for the children fallen from grace.”

At the height of the crisis, clubs weren’t just havens for dancing, they became health centers, information hubs, and sanctuaries from an increasingly hostile political climate.

Major parties raised vital funds and awareness, turning house culture into a frontline of resistance.

Photographer Melissa Hawkins remembers: “Every week you would read pages of obituaries. Then, at night, you would go to the most fantastic parties. That was when people really lived in the moment because you never knew how long you had.” So, when Mr. Fingers asked Can You Feel It?, it was far from rhetorical. When Marshall Jefferson said Move Your Body, it was a command. Whoever was behind the decks was issuing a call: to resist the countless ways people were being divided, to mourn, to surrender to the rhythm.

As Vince Lawrence beautifully puts it, “For me, house music is the definition of the word intersectional. House music knows no race, it knows no social economic status. It knows no sexual preference, no religion. House brings everything and everybody together despite any so-called or perceived differences. When you’re one with house music, it’s all about that beat and the release and the spirit of music moving through you and all of the things that separate us kind of fade away underneath the boom, boom, boom, boom.”

From Chicago with Love

Some of the most iconic boom boom boom boom sounds of the time were released through labels like DJ International Records and Trax Records. Thanks to these records, the styles pioneered by Chicago producers spread beyond the city, especially to Detroit, New York, and London.

As house music carried its momentum into the 1990s, artists began touring internationally while new subgenres were being heard that would shed light on today’s scene. Like deep house, which took off in the 2010s and brought a deeper, more emotional sound to the tracks, and ghetto house.

In the mid-90s, ghetto house hit hard—raw, unapologetic, and hypersexual, with BPMs exceeding 140, capturing the unfiltered truths of Chicago’s streets.Another major rise came through acid house, defined by the distinctive squelch of the Roland TB-303 synth.

Chicago house had ignited a cultural revolution in the UK, laying the foundation for acid house and the explosion of rave culture. When rave culture migrated to the U.S. in the 1990s, Chicago house revived after a few years of stagnation. DJs began revisiting the roots, weaving classic house tracks back into their sets. By 1993, the city was experiencing its second spring. The talents of that era created a tsunami that would hit the whole world with terrific house tracks.

The second spring of the city

This global success brought both opportunities and challenges for Chicago artists. Many saw their work exploited by major labels without fair compensation.

“One thing my generation learned was to put out our own [music]. A lot of independent labels that were birthed from the fact that people got ripped off in the early days of house music,” says Braxton Holmes.

One example was Cajual Records, founded by Green Velvet (aka Cajmere), a driving force of Chicago’s second wave.

The label’s first release, The Percolator, shook the city, followed by Dajae’s uplifting anthem Brighter Days, which soared to number two on the Billboard dance charts.

These hits made it official that the city’s second spring had arrived. Next in line were Glenn Underground, DJ Sneak, and Derrick Carter, rising from local neighborhoods to global stages. Many of these artists earned their stripes at legendary clubs like Foxy’s, Shelter, and Smartbar.

They launched labels such as Relief, Gramaphone, Guidance, and Prescription, each wave of artists taking up the house mantle and passing it along with fresh spirit to the next generation.

Longing For Better Content?

No one belongs here more than you do.

Read thought-provoking articles that dissect everything from politics to societal norms. Explore critical perspectives on politics and the world around us.

Also, you can follow us on Instagram

1 Comment

Note: Welcome to Edito, the written space of Literal Radio that centers music-shaped, evolving, and deepening cultures. Every two weeks, you’ll be invited into the stories behind genres, scenes, and sounds. Enjoy the read.